Fantastic Tractor Dogs and how *not* to find them

Modern vision models can detect almost anything you name — tractors, dogs, traffic cones — even if they were never explicitly trained on them. But there’s a catch. When you ask these models to find something that isn’t in the image, they often refuse to say “nothing”. Instead, they confidently point to the wrong thing. A dog becomes a tractor. A shadow becomes a suitcase.

This new work shows why. In open-vocabulary detectors, language and vision are mixed early inside the model using attention. The words you provide don’t just guide the model — they leak everywhere, nudging it to find a match even when none exists. The model isn’t hallucinating at random; it’s being gently pushed into seeing patterns that aren’t there.

The fix turns out to be surprisingly simple. The authors introduce attention sinks: special tokens added to the prompt that act like drains for misplaced attention. When there’s no real visual match, attention flows into these sinks instead of being spread across the image. No retraining, no new data — just a smarter way to control where attention goes.

The result is a big drop in false positives and a model that’s much better at admitting when something isn’t there. Sometimes, making AI more reliable doesn’t mean teaching it more — it just means giving its attention somewhere safe to go.

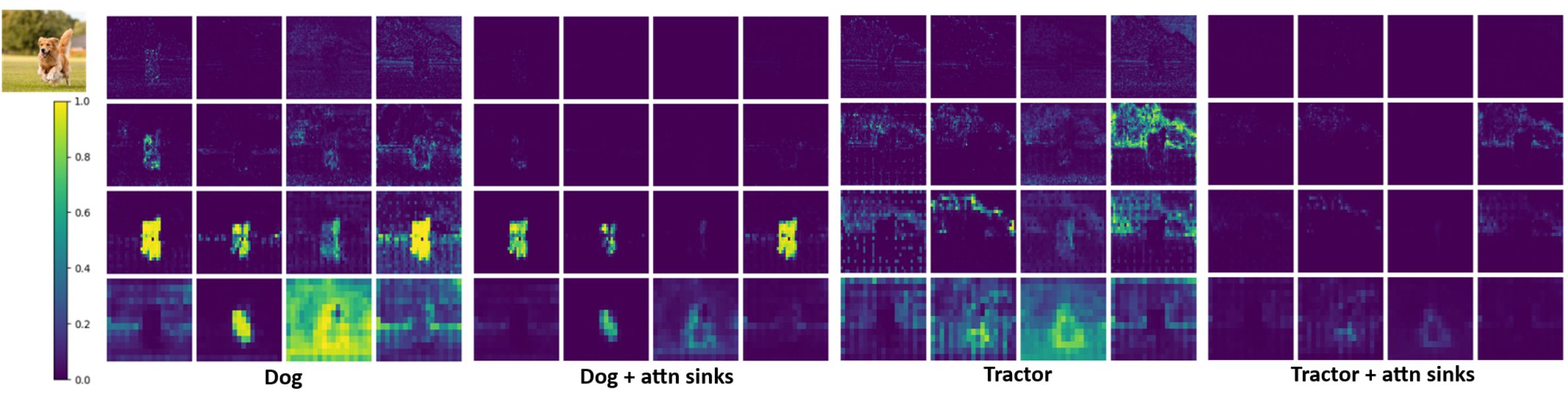

A visualisation of the attention scores of each head (horizontal) and scale (vertical) from the first vision-language fusion layer of LLMDet, between the visual features of an image of a golden retriever and the prompt tokens “dog” and “tractor”, without using attention sinks (left) and with attention sinks (right). Both the positive and negative class have a much cleaner attention map after adding attention sinks, with most irrelevant information (in case of the tractor prompt) being routed away from the negative classes to the attention sinks.

Accepted at ICLR 2026, see Publications.